Key Concepts in I.B. Geography

Introduction to Key Concepts

The opportunity to have concepts in the foreground of the curriculum topics and the focus for geographic inquiry allow for more discussion, application of thinking skills, and transparent assessments. Students are required to discuss or evaluate in a way that shows conceptual insight into the context of the expected knowledge and understanding. The application of geographic skills allow for the synthesis of knowledge and ideas, and bring understanding of concepts and contexts together through the study of specified or appropriate content.

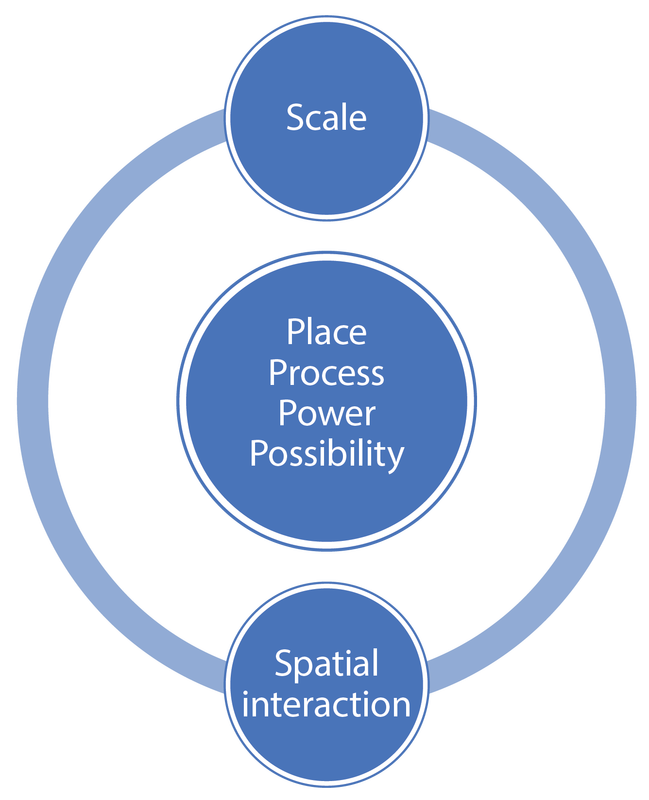

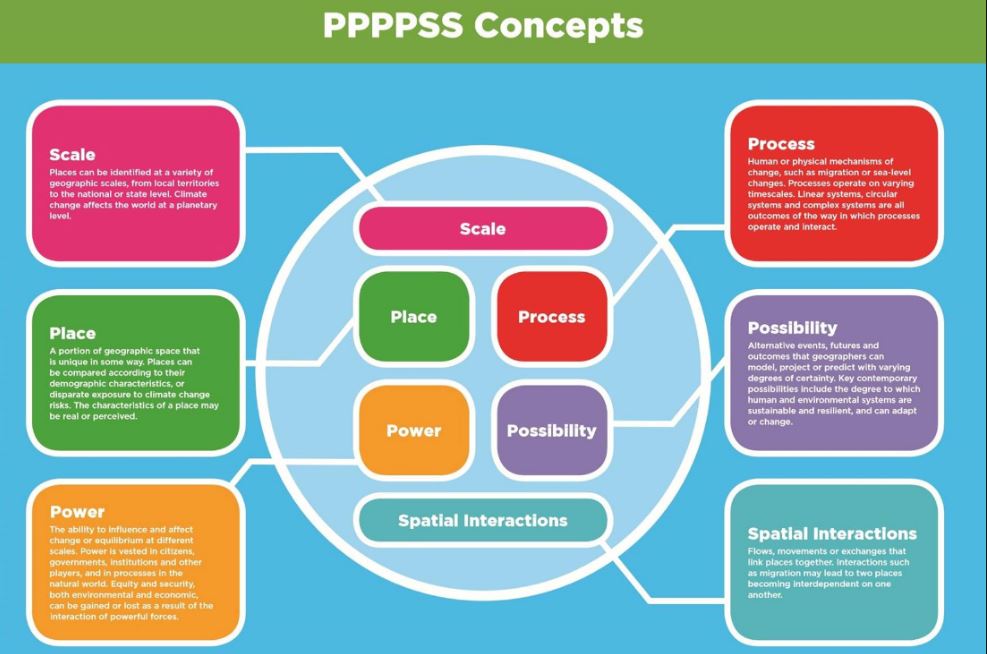

The “Geography concepts” model (above) shows the six main concepts of the course, with the four key concepts of place, process, power, and possibility at the centre and the organizing concepts of scale and spatial interactions connecting them. Scale has both temporal and spatial perspectives.

Places can be identified at a variety of scales, from local territories or locations to the national or state level. Places can be compared according to their cultural or physical diversity, or disparities in wealth or resource endowment. The characteristics of a place may be real or perceived, and spatial interactions between places can be considered.

Processes are human or physical mechanisms of change, such as migration or weathering. They operate on varying timescales. Linear systems, circular systems, and complex systems are all outcomes of the way in which processes operate and interact.

Power is the ability to influence and affect change or equilibrium at different scales. Power is vested in citizens, governments, institutions and other players, and in physical processes in the natural world. Equity and security, both environmental and economic, can be gained or lost as a result of the interaction of powerful forces.

Possibilities are the alternative events, futures and outcomes that geographers can model, project or predict with varying degrees of certainty. Key contemporary questions include the degree to which human and environmental systems are sustainable and resilient, and can adapt or change.

Places can be identified at a variety of scales, from local territories or locations to the national or state level. Places can be compared according to their cultural or physical diversity, or disparities in wealth or resource endowment. The characteristics of a place may be real or perceived, and spatial interactions between places can be considered.

Processes are human or physical mechanisms of change, such as migration or weathering. They operate on varying timescales. Linear systems, circular systems, and complex systems are all outcomes of the way in which processes operate and interact.

Power is the ability to influence and affect change or equilibrium at different scales. Power is vested in citizens, governments, institutions and other players, and in physical processes in the natural world. Equity and security, both environmental and economic, can be gained or lost as a result of the interaction of powerful forces.

Possibilities are the alternative events, futures and outcomes that geographers can model, project or predict with varying degrees of certainty. Key contemporary questions include the degree to which human and environmental systems are sustainable and resilient, and can adapt or change.